By Jim Embry

During the Biodynamic Conference on Friday. November 16, I will be presenting a workshop, George Washington Carver and the Biodynamic Movement. What I will attempt to do here is provide a “pay it forward” invitation for conference attendees to drink from Carver’s cup, which has been grossly neglected and misunderstood for so many years.

Why is it important for the biodynamic movement to embrace George Washington Carver and his huge body of work? There are numerous reasons; I will pour just a few sips.

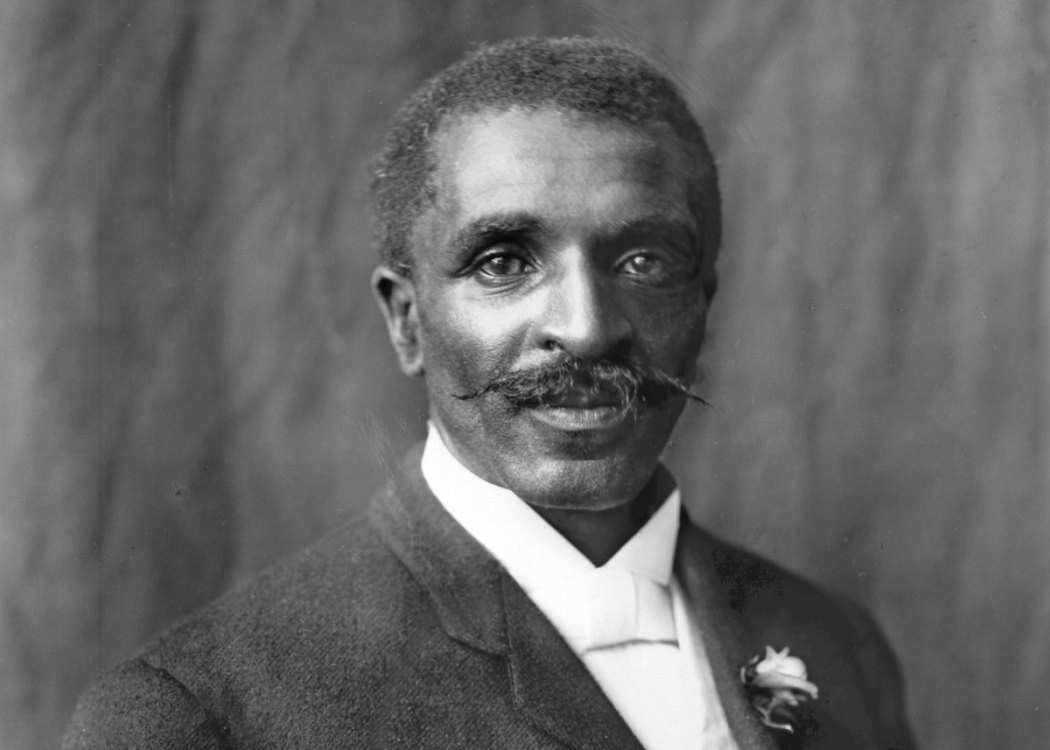

The conference theme Transforming the Heart of Agriculture through the lens of Soil, Justice, and Regeneration is precisely what Carver was doing for almost fifty years (1896-1943) while working at Tuskegee Institute. Carver clearly understood the interconnectedness between soil, justice, and regeneration, especially for “his people,” the formerly enslaved Africans in the South. Using Carver as a lens, we can get a glimpse of his Progressive-era efforts to navigate the intersection of land use, race, and poverty in the rural South as part of the larger conservation and sustainable agriculture movement. Carver’s campaign on behalf of impoverished Black farmers and soil in the South can serve as an instructive model for how to transform agriculture and our people today.

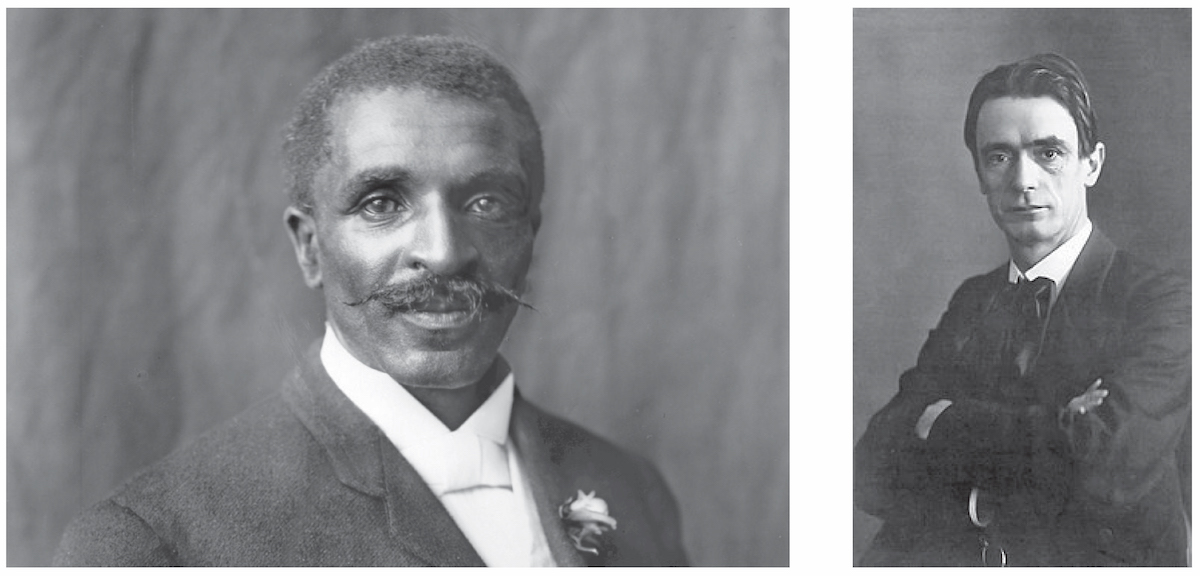

George Washington Carver (http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1064) and Rudolf Steiner (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolf_Steiner)

Carver and Steiner shared similar life pathways, were contemporaries, and held very similar views and practices regarding the spiritual and scientific dimensions of agriculture. Steiner was born in 1861 of “peasant stock,” studied botany and other sciences at the Vienna Institute of Technology. Carver, enslaved at birth with no official birth record, but born between 1860 and 1864, also studied botany and other sciences at Iowa State Agricultural College.

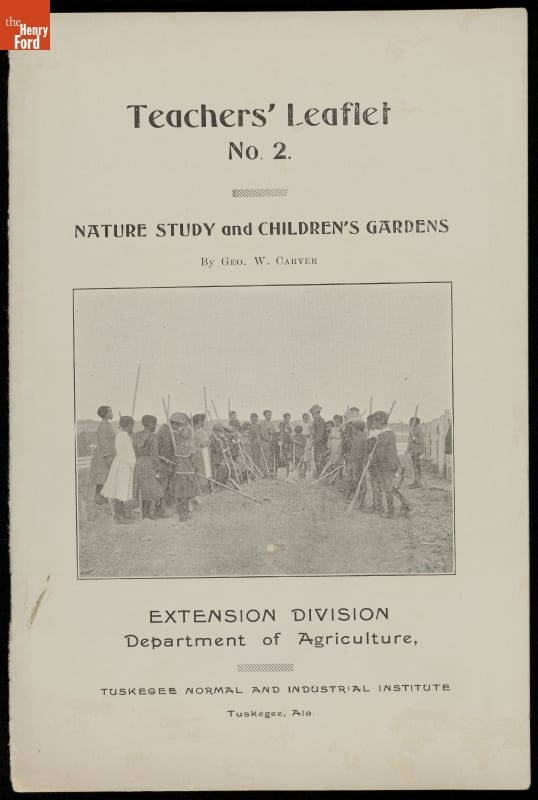

In 1924 Steiner delivered his eight lectures, which became the Agriculture Course. As an early proponent of organic agriculture practices, Carver encouraged farmers in 1898 to “look at the permanent building up of our soils,” and he warned that heavy reliance on commercial fertilizers would lead to a soil “collapse.” Carver wrote (and drew illustrations for) forty-four agricultural bulletins while at Tuskegee, which covered topics such as trees, plants, farm animals, fungi, nature study, food preservation, composting, and soil fertility. Carver also organized more formal methods to reach the rural population, including the Annual Negro Farmer’s Conference (1892), the Monthly Farmers' Institute (1898), and the Farmers' Short Courses in Agriculture (1904).

(https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/pamphlet-nature-study-and-childr...)

In Lecture Seven of the Agriculture Lectures (referred to by some as the “permaculture” lecture), Steiner described the importance of fungi within the farm community. Carver's Master's degree thesis at Iowa State was on fungi, and two species of fungi were named after him because of his important work in this area.

Carver and Steiner both understood the need to provide an educational experience for children that included an eco-agricultural curriculum. In 1919, Steiner worked with others to establish the first Waldorf School in Germany. Carver was an important contributor to the US nature study movement and in 1898 prepared his first bulletin on nature study and school gardens for children. They both developed important relationships with business philanthropists. The Waldorf Schools were so named because of the initial connection with the Waldorf-Astoria Cigarette Company. The Jesup Agricultural Wagon, Tuskegee’s agricultural school on wheels that Carver created, was named for the New York financial benefactor, Morris K. Jesup.

(http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1064)

Both Carver and Steiner recognized that spirituality and science were not antagonistic, but an expression of a cosmological “unity.” Carver called his laboratory at Tuskegee God's Little Workshop. From his bachelor thesis in 1894, Carver writes: “Man is simply nature's agent or employee to assist her in her work. Hence the more careful and scientific the man, the more valuable he is as an aid to nature in carrying out her plans…all flowers talk to me and so do hundreds of little living things in the woods. I learn what I know by watching and loving everything.”

(http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1064)

Carver’s first love was art. He studied music and art at Simpson College and became an accomplished painter, exhibiting his art at the 1893 World’s Fair. Steiner was also an accomplished artist who created wooden sculptures, wrote plays, designed buildings, and developed the art of eurythmy. Carver’s bulletin illustrations and Steiner’s blackboard drawings would have been but one source for exciting conversation if they had met.

As a much sought-after herbal healer, Carver would have been right at home with the biodynamic preparations. But today we need new biodynamic “preparations” for equity, inclusion, indigenous thinking, food sovereignty, and climate change. Mahatma Gandhi asked Carver for advice about how he could build his strength between hunger strikes. Our understanding of Carver could serve us as well, as we hunger for insight into regenerating our relationships with each other and the soil.

Lastly, George Washington Carver is not mentioned at all in writings that describe the history of organic farming, conservation, and environmental education movements in the USA. What a disservice to someone who contributed so much! Too many teachers and writers in regenerative agriculture write about the important work of Albert Howard, J.I. and Robert Rodale, and Bill Mollison as part of the organic agriculture movement, but do not mention George Washington Carver. I invite them and other conference attendees to join me in the Carver cornucopia that my workshop will offer.

Jim Embry, who considers himself stardust condenses in human form, was born in Richmond, Kentucky, a grandson of small farmers who were also social activists. This family legacy of activism was passed down to him as a 10-year-old participant in the Civil Rights Movement. Often times called an “eco-activist” or labelled as Black & Green, Jim has worked to connect social justice, food justice and environmental justice within other social movements for the past 50 years. Jim now serves as director of Sustainable Communities Network and cultivates collaborative efforts at the local, national, and international levels with a focus on food systems. He is at home at every level, whether as a five-time USA delegate to Slow Food’s Terra Madre in Italy, a visitor to Cuba to study organic farming, his extensive work in urban agriculture, or planting on his 30-acre farm, Jim maintains that the local food and sustainable agriculture movement is the foundation of a sustainable community. His belief is that we need some big ideas that connect humans in a sacred relationship with the Earth, which will require us to think not just “out of the box” but “out-of- the-barn”.

Jim Embry, who considers himself stardust condenses in human form, was born in Richmond, Kentucky, a grandson of small farmers who were also social activists. This family legacy of activism was passed down to him as a 10-year-old participant in the Civil Rights Movement. Often times called an “eco-activist” or labelled as Black & Green, Jim has worked to connect social justice, food justice and environmental justice within other social movements for the past 50 years. Jim now serves as director of Sustainable Communities Network and cultivates collaborative efforts at the local, national, and international levels with a focus on food systems. He is at home at every level, whether as a five-time USA delegate to Slow Food’s Terra Madre in Italy, a visitor to Cuba to study organic farming, his extensive work in urban agriculture, or planting on his 30-acre farm, Jim maintains that the local food and sustainable agriculture movement is the foundation of a sustainable community. His belief is that we need some big ideas that connect humans in a sacred relationship with the Earth, which will require us to think not just “out of the box” but “out-of- the-barn”.

Jim will also be featured at the Biodynamic Conference during the keynote presentation, "Biodynamics, Indigeneity, and Social Justice," on Saturday, November 17.

Comentarios

Kelle Jolly (no verificado) said:

We need to uplift the work of George Washington Carver to heal, especially at this time.

GigiDear1 said:

Thank you for this inspirational look at George Washington Carver and the parallels with Rudolf Steiner. I hope to learn more about Dr. Carver. Book recommendations would be useful.

I hope to pass along any information I learn to the local community. I am currently an active BDA member nationally and locally, but have had to step back from activity during the pandemic. This is a great time for reflection and sharing.

I am going to be involved in an Extension panel on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion this year and I am looking for ways to reach out to communities to further social justice in this area.

Thank you!

Añadir nuevo comentario