An interview with Thea Maria Carlson, Executive Director of North America’s Biodynamic Association

By Rebecca Reider

Originally published in the December issue of Harvests Magazine, published by Bio Dynamic Farming and Gardening Association of New Zealand

The following interview has been edited for length, and lightly edited for clarity.

Rebecca Reider: How has your approach to communicating biodynamics evolved?

Thea: My experience has been most people, even if they’ve been practicing biodynamics for years, they still feel like they don’t know very much…. Even before I worked at the Biodynamic Association, I taught school gardening and I taught beekeeping and composting, and with all those things I learned a little bit and then I would start teaching it; but it seemed like with biodynamics you never know enough to be an expert and so… I think for me one of the hurdles was just recognizing that I did know enough to be sharing, even though there’s always more to learn.

Another aspect for me is I had a very traditional science training in university, and so reconciling that with the more esoteric ways of describing biodynamics was something that I felt was important. I know there are some people who pick up Steiner and completely resonate with everything and they’re totally in, but that wasn’t me, and so I figured there were a lot of other people like me…. I really needed the experiential component of being on biodynamic farms and seeing that vitality. And so if people aren’t going to first be on a farm, how do we give them an experience of biodynamics rather than talking about abstract concepts that are hard to ground?

And then one of the things that is generally great about my role with the Biodynamic Association, having these conferences where we have 40 or 50 or 60 workshops, is getting a whole bunch of different people, hearing how they present biodynamics and picking out ‘oh this, this thing resonates with me; this resonates with me’.

RR: You spoke in your talk about the concept of your organization as a living organism. Can you say more about how that works in practice? How do practices that you’re using in the organizational realm match up with biodynamics?

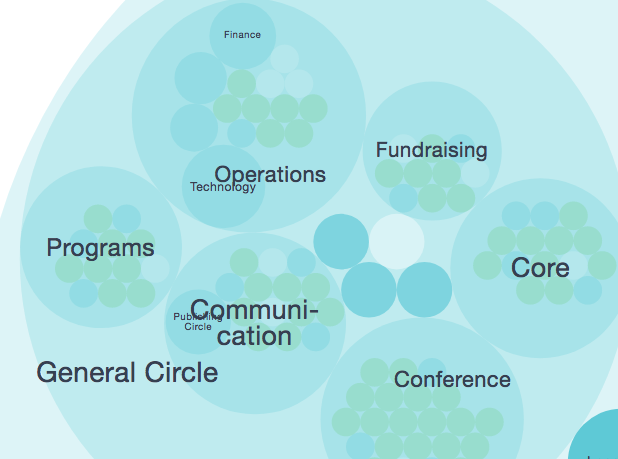

Thea: When you’re farming, you’re not telling the plants how to grow, right? And you’re not telling the animals how to be; you can’t, because they’re not people…. It’s like a healthy farm; the farmer is not in charge… but more creating the conditions for everything to thrive in, figuring out how the different organs of the farm can relate to each other and attending to the health of the whole and noticing what’s missing. And as a leader of an organization I wanted to be more in that model, rather than ‘here’s our factory and this happens and then this happens and this happens and we always get the same output’.

It requires a degree of trust that I think is challenging, but it’s necessary and I think that’s something that being a farmer I’ve learned…. There’s only so much you can control, and if you try to control it too much, it’s just going to backfire. If I want my goats to express their full goatness, what do I need to do to support them, instead of being like ‘you must go over here’ – and of course you might be able to get them to go over there, but they’re going to be dragging their feet the whole way, and it’s a lot of extra energy for maybe not the best result.

RR: But what happens – you’re the director – what happens when you disagree with the way someone is doing something? If you’re informed by ‘our organization is an organism’, how do you interact differently?

Thea: I think it’s coming from more of a perspective of coaching rather than managing, and that it is really important to find ways to help everyone sense into the whole because if we’re not all connected as a whole, then it’s not an organism… it’s just a bunch of people doing stuff that’s vaguely related. So there is a lot of connection and sensing that needs to happen. I would say everyone in the organization actively seeks my input on a lot of things and values my opinion, so it’s not like I don’t have power; it’s just how I’m using the power. And so often people will approach me when they’re not sure what to do about something, and then my general approach is rather than saying ‘Well this is what you should do’, just asking them questions to help them get closer to an answer that makes sense to them, depending on how much time we have and whatnot. Sometimes it’s just ‘Well I think we really need to do this’ so, there are limits to it.

But if someone’s doing something that I have some tension around, one of the things that comes out of Holocracy that I find really helpful is the concept of tension as the energy that makes things happen…. If someone else in the organization is doing something that’s really not sitting well with me, I try to first understand for myself what about that is not sitting well with me, and then approach them and say ‘Hey, you know I have some tension around this’, and because we have that language it’s less personal, it’s just like ‘I’ve got this tension and I want to share it with you’… and then engage in a conversation and try to understand why they’re doing things the way they are. And sometimes that leads to them changing what they’re doing, and sometimes it leads to me having a better understanding of why they’re doing what they’re doing… and sometimes I say, ‘Well you know, if it was me, I would do this, but you make the choice’. It’s not by rote…. It’s a dance that we’re all learning how to do all the time.

RR: Justice is one of the themes of your upcoming conference. How has that come up, and how are you exploring that?

Thea: It’s something that’s very much emergent in food work in general in the United States, but in biodynamics as well. It’s something that within our organization showed up in numerous ways over the past few years, and then this year multiple members independently approached me around this idea of social justice and how we’re connecting with social justice. In the United States there’s just so much of the many centuries-long trauma of racism really coming to the surface in a new way and causing a lot of white people to wake up to that, the injustice that we’ve been part of, usually unwillingly, and most of the time unknowingly, and a sense that we can’t just keep going on as if it’s not happening and that in order for us to move forward with integrity we really have to address it….

The way it emerged for me in my work was our 2014 conference… the theme was Farming for Health and we had this doctor, Daphne Miller, who had spent a year spending time on different farms, including a biodynamic farm, and drawing connections between how farmers care for their land and how we can care for our bodies. And so she had this whole presentation, a keynote speech, I think it was the morning of the first day of the conference, and she had all these slides showing this research about microbial diversity and health. So kids who grow up on a farm have less asthma and allergies than kids who grow up in the city; they’re exposed to the same number of microbes, but in the city it’s a really small variety, large number; and in the farm it’s a large number but many more species, and that’s healthier. And then at the end of the conference, there was a participatory session, and there was a man who got up who was one of maybe two or three black people in the audience of 600 people and said, ‘Okay you’re talking about microbial diversity. Let’s look around this room; this room does not have the diversity it needs for this movement to be healthy.’ And as the organizer of the conference I just was filled with shame, and just felt really terrible that he was pointing out this really hard truth, that we were in Louisville, Kentucky – there are historically black colleges quite near to Louisville – but we hadn’t managed to get many of those people to be in the room, and I felt really bad about that.

A full year later… I went to a leadership retreat and was doing some contemplation about my work and what was important, and it really showed up for me that I needed to address this issue of diversity, and so I decided at the retreat I was going to call this guy, figure out who he was and actually have a conversation with him because I hadn’t spoken to him at the conference…. I finally found his phone number and gave him a call and had just a lovely conversation with him, saying ‘Thank you so much for this comment. It was really hard for me to hear, but I really want to do things better; what do you think we should do?’ And he said, ‘Well you’ve got to start with who are your presenters and keynote speakers. If people don’t see people who look like them who are presenting, then they’re not going to want to come. And then you really need to connect with organizations that these people are already involved with and you need to give people scholarships so that they can get there.’

And so that was a really big focus for me for our 2016 conference. [There’s been a pattern in organizing conferences that] the people who know about biodynamics, they just happen to all be white men, so we can’t have anybody else on because we need people who know about biodynamics and it’s kind of like this vicious cycle, right….

So in order to increase the diversity of gender and racial demographics of our speakers, it meant that we had speakers up there who maybe didn’t know very much about biodynamics, but they knew stuff about other things that were interesting. We had a white doctor come and talk to us about farming for health and we had a white guy in 2012 talking about economics, so it’s not like it was unprecedented that we had people who were outside of the biodynamic community… [For the 2016 conference] we changed our scholarship application form so we asked people about their racial/ethnic identity if they wanted to share that, and then really made sure we prioritized outreach especially to Indigenous and Hispanic communities around New Mexico [where the conference was held], and definitely, it was a much more diverse conference in 2016 than 2014.

RR: What’s drawing people to biodynamics in the States at this time? Do you see any generalizations or patterns?

Thea: I think there are a few things…. There’s a general trend towards people being more interested in where their food comes from and connecting to agriculture, so that’s one factor. I think there’s also a huge number of people now who are more interested in yoga and meditation and connecting to spirituality in that kind of way, which I think lends itself to the spiritual dimension that’s present in biodynamics … When it’s shared in an open and approachable way there are a lot more young people who are feeling the lack of a spiritual dimension to most things in modern society and looking for that… that’s something I’ve noticed in terms of who shows up at the biodynamic workshops that I do at farming conferences and the kind of questions that people ask. They are really actively interested in what does it mean for agriculture to have a spiritual dimension, and can that fulfill something that feels like it’s missing in how we approach everything in modern society?

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Joanne Turner for transcribing this interview.

Comments

neebee said:

I've always had profound respect for Biodynamics, and yet only recently have delved into ALL that the name implies... having begun the Biodynamic Beekeeping training at Spikenard, it is crystal clear to me that the way in which we articulate the things that differentiate/distinguish Biodynamics is really, really vital. It is important that we foster the willingness/openness with which we are received by folks new to such notions by inviting them to consider divergent perspectives rather than conking them on the head with them...

Add new comment